Two weekends ago, New Jersey-based pro fighter Anthony Montanaro was stuck in hell.� He and over twenty other people were confined to the matted-space within the four walls of a massive gym, and every hour for twenty-four hours straight, all were subjected to workouts of varying length and composition.� There were seven-minute wrestling matches.� Rope climbs.� Box jumps and pull-ups.� The works.� No sleep was allowed, and men broke, both physically and mentally.� Yet, despite being driven to the brink of madness, Montanaro pushed through, and when the last workout was done and they were all permitted to leave, he was stronger because if it.� Such was the magic of the 24-hour lock-in.

�

"A 24-hour lock-in is your worst nightmare amplified by ten," says the 25-year-old Montanaro, who, with a shaved head and the tattoo of an armored pitbull on a chest, looks every bit the MMA fighter archetype.� "It's twenty-four hours straight of nonstop training, where every hour on the hour you have a different workout that could be five minutes to a half-hour long.� The whole purpose is to break you, to make you hit the wall as soon as possible.� It's all mental toughness.� It's a nightmare."

The Rhino Wrestling Club in Morganville, N.J., was where this nightmare unfolded; the day began Saturday morning at 9:00 a.m. and went until 9:00 a.m. Sunday morning.� It was rigorous, with the intense physical activity and sleep-deprivation aspects making it more akin to what a soldier would do for Special Forces training than anything else.� "I don't know if they stole the idea from Navy SEAL-type stuff, but it was ridiculous," says Montanaro.� "It was kind of like the whole Marine or Army crucible-type stuff, know what I mean?"

To prepare for fights, fighters go to great lengths to make themselves like steel.� There's roadwork, padwork, grappling, and as we've seen on "The Ultimate Fighter", conditioning drills that can involve things like flipping giant tires and swinging sledgehammers.� With a fight coming up in the next few months, Montanaro is no different.� But what benefits are derived from the lock-in?� Clearly, the limits of the conditioning of the participants are pushed, but is there something more?�

"Honestly, just complete mental toughness," says Montanaro. �"You get to a point where you don't think you can go anymore and then you have to go.� It's insane.� It's probably the worst training I've ever done.� I was more nervous for that than any fight I've ever had to do."

What of the necessities of human existence?� "They have a bathroom, of course," says Montanaro.� "Food's included? all the food you can eat.� After your workouts, even if you weren't hungry, they stressed that you drink and eat nonstop ? just carb you up and keep you going.� Sleep, that's not encouraged at all.� They keep you awake, keep you zombified, keep you going."

Obviously, the whole endeavor was tortuous.� Was there any particular thing that Montanaro found to be the toughest?� "The toughest thing about the lock-in?� Where do I even start?� The whole damn thing.� Once you hit that first wall, that's when it's brutal.� Everything hits you all at once ? you want to sleep, you try to lay down and it's time for the next workout.� I would say around two or three in the morning, that's when it's the worst.� You know you could just leave at any point you want, but it's just that whole mental aspect."�

If one could literally leave at any time, it sounds as if the name ? a "lock-in" ? is a bit of a misnomer.� "It was going to be a complete lock-in, but it was so damn hot, there was no way they could do something like that.� We would've kicked the doors down.� There was no way."

With door unlocked and retreat requiring only an exit through the door, did anyone quit?� "No, surprisingly enough, no one quit.� And the craziest thing was there was an 11-year old kid there.� Some parent signed their kid up to do it!� It was the most ridiculous thing I've ever seen.� So anytime someone wanted to quit, we'd look at this little kid.� He was our mascot."

What was the atmosphere like?� Was it all business, or was there at least some of element of fun to it?� "For the first probably like eight to ten hours, everyone was kind of feeling each other out ? you know, like, is everyone in full serious-mode or are we going to have some kind of�fun here?� Probably at night is when everyone started to get a little loopy.� Everyone started to get punchy.� The later it got into the night, everyone was just out there."

Would Montanaro go through it all again?� "Absolutely," he says without hesitation.� "In a heartbeat.� After it was done, I honestly just wanted to stay and keep going.� It's just nonstop training, no drama, no [expletive], everyone was just there to train.� If we could do it, I would love to do it every month."

A wise man once posed the question, "Do you want to be a [expletive] fighter?"� It's doubtful he'd dare ask that of Montanaro and participants of the 24-hour lock-in.

donate a car san francisco

YouTube Blog | Email this | Comments

YouTube Blog | Email this | Comments

"Making this funeral for Rafinha hardly expresses what she represented in our lives in these five years."

"Making this funeral for Rafinha hardly expresses what she represented in our lives in these five years."  From raw lasagna to spicy cherry gazpacho, keep the kitchen cool and power-usage low with the best of summer non-cooking.

From raw lasagna to spicy cherry gazpacho, keep the kitchen cool and power-usage low with the best of summer non-cooking.

When you are carrying everything on your back, you learn quickly what's really important.

When you are carrying everything on your back, you learn quickly what's really important.

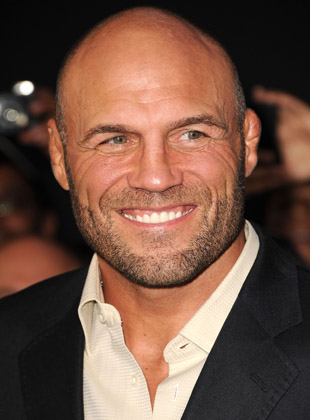

You will be disappointed if you want to see UFC Hall of Famer Randy Couture fight again. He is focused on his movie career, and recently told me he is starting to feel more like an actor and less like a professional athlete.

You will be disappointed if you want to see UFC Hall of Famer Randy Couture fight again. He is focused on his movie career, and recently told me he is starting to feel more like an actor and less like a professional athlete.